I was pointed at this auction by a fellow collector who

only knew I was looking for one because when you search for 'Tandata PA' the

only hits were these very pages, cheers Tony!

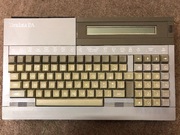

It's an NEC V20 powered machine which means its 8088

compatible (the V20 is a reverse engineered 8088 clone) with a Thomson EF9345P

display controller and battery backed up RAM coupled with a big battery pack to

make it portable to a degree. In the words of Nick Walker who reviewed it for

PCW magazine back in 1986 'it's the best phone I've ever used.'

Check out the review here.

They're in alphabetical order so just scroll down.

I now hand this page over to former Tandata developer Boc

who spent many years working on the PA and quite rightly thinks it's an under appreciated machine.

There's a reason I've wanted one for this long!

I am really very pleased to see someone interested about the

particular dead branch of computing history known as the Tandata PA. I

spent many years working on it, among others, and I don’t think its

importance as a historical artefact is appreciated.

The fact that it was designed and built by a company that was only

known for Viewdata-type terminals means it is often confused with

being just another terminal. The thing to understand about the PA is

that it was a portable computer – what we would now call a laptop.

Admittedly, a portable computer optimised for communication with host

systems cleverer and more capable than it.

For context, Wikipedia says that the first recognisable laptop –

battery powered, LCD display, for use on the move (as opposed to the

“luggables” that could be carried from office to office and had to be

plugged to a socket for use) was the Epson HX-20, announced in ’81 and

widely sold in ’83. Development started on the Tandata PA in the

second half of ’82 but only really kicked off in early ’83. The

product was finally launched in the back end (October?) of ’85 and

sold from early ‘86. The first and only UK entry in the Wikipedia

history of laptops article is the Clive Sinclair designed Cambridge

Z88, first sold in 1988! The Z88 is also credited with being one of

the first PDA’s – ha! The clue’s in the name – Tandata P.A.

So, the Epson HX-20 had a 20 character by 4 line LCD display. The

Tandata PA launched two years later had only 20 characters by 2 lines,

but it was a very different beast at a time when it really wasn’t

clear what a portable computer should be. The Tandata PA was all about

comms.

Comms and Email in the early 80’s was very different from today – no

internet! BT operated the Viewdata service, which was mostly about

looking up things – it was connected to Travel agents, so you could

browse and book holidays, it was connected to the Bank of Scotland, so

if you had a special account you could see your account and even could

pay bills! It also had a rudimentary email system where you typed into

a fixed-size small box on a screen, and sent a message to another

Viewdata user whose email address you remembered. The service was

mostly aimed at consumers. There was a second system in the UK, BT

Gold from BT. This was no more and no less than a login to a timeshare

computer. You dialled up and were presented with a simple flashing

prompt. If you typed “mail” you entered the email programme. You typed

live into the screen, and pressed control-Z at the end to send. But

only, of course, to other BT Gold subscribers on the same system.

Because BT Gold email was not limited to a single screen of text, it

appealed more to commercial users.

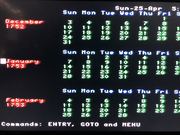

We judged the small LCD display on the PA was sufficient for portable

input and editing of messages - offline and battery powered. No

“mobile data” obviously, but with the PA you could create a message

while on the train during your morning commute, and when you got to

your office you plugged it into the phone socket and sent it.

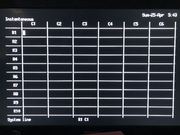

Revolutionary! In addition to the word processor you also had a

calculator with paper roll history, a phone book, a diary with

settable day and time reminders and even a spreadsheet – everything a

busy executive could need to set up his day in the office. When he

(always a he!) gets to the office, plug it in and you had a modem to

dial, a 40x24 colour screen for Viewdata data lookup, a 80x25 mono

display screen for BT Gold, RS232 to connect directly to the company

mainframe with Dec VT-100 and IBM 3270 compatibility, a printer port

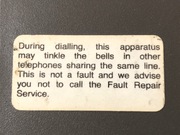

(inside your office it would be completely paper driven), and the

least-understood part of the design, a second, pass-through phone

socket. Plug your standard desk phone into this socket, and the PA

would monitor the activity, noticing if you picked up the phone and

offer to dial for you, or dial from the phone book, etc. The original

design even included a loudspeaker and microphone to act as a

loudspeaking phone, however the approvals process needed to get a

fully functional active phone approved for connection to the BT

network was too onerous, and the microphone had to be dropped. With

this understanding you can see the reasoning around the decision the

device was most criticised for – no removable storage media. You do

not need to keep data on the device long term – you upload it (or

“send Email” as we would now say).

Finally, (ta-da!) the PA was not only multi-tasking and multi-user,

but even “timesharing”, potentially enabling a Manager and a secretary

logging into the same PA at the same time to edit different documents!

Try doing that even with modern laptops without a server. Nowadays the

device would have been subject to a whole bunch of patents but in

those simpler times software patents were simply not considered.

So what went wrong? Two things. Mostly, the market was not ready. The

need for a portable device was not developed – our Unique Selling

Point of a portable device was a curiosity not a must-have. I remember

we launched with a full-colour A4 glossy of a man (told you) sat on a

train, typing. I would love to see a copy of that preserved on the net

somewhere, but it is almost certainly lost. However the initial

reviews instead focussed on the PA as an up-market “executive”

viewdata terminal. In the absence of market excitement, Tandata soon

retreated to its core market of Viewdata users. In the Wikipedia

article it is notable how many of the early devices were failures to

some extent or other. The market for battery powered mobile devices

was not ready.

The second thing that went wrong was a famous random failure mode

discovered just after launch that took too long to fix, an unfortunate

combination of being too ambitious and plain bad luck. The PA was

designed never to be really switched off. Almost (totally?) unheard-of

at the time, there was no power switch, just a signal switch that

basically said the user wanted the system to enter a low-power mode

(now familiar on laptops as stand-by mode). This was needed because

the PA had a real-time clock and was supposed to wake up for diary

alarms and even auto-answer the phone. That was the ambition. The bad

luck, was that the physical design required the PCB to be mounted

upside down in the case. Not a problem usually, but the software was

burnt into eproms and so sockets were used to enable the software to

be upgraded. If the PA was dropped hard onto a desk, the eproms might

loosen in their sockets for an instant and if the PA happened to be on

at the time it would briefly execute random electrical noise. A

disastrous event for a machine designed to be moved with no backup

media and no hard reboot button. With such complicated software

obviously we thought it was a software bug not a hardware fault. It

took us months analysing return-to-factory units – all we could ever

see was that for some mysterious reason the CPU had taken a

machine-gun to the filing system. Solved eventually of course but the

damage was done. The first production run was 1000 units (not bad

income at almost £1000 a pop), and I think there was a second run, but

that was it. However I do know every single PA was sold, which is why

there are so few left now. The big companies who bought the PA’s in

bulk would have disposed of them responsibly after many years of

dedicated use. There was never even a small pile of unsold units for

the enthusiastic amateur to salt away.

Sorry about the above screed of text, but as you can see I think that

the innovations of the device have never been recognised. I always

wanted to amend Wikipedia to include this UK first, however Wikipedia

is not the place for original work - it needs to reference definitive

articles elsewhere on the web, and no such web page has ever existed

for the PA. Perhaps if you publish such an article, you and I can

right this historical record injustice…

On to your device: It seems an early model with upgraded software. The

EPROM marking is fascinating – DENIS means nothing to me anymore but

we were very fond of puns and jokes so it probably meant something

funny. The important part is the V1.3b designation. There was never a

V2, but I remember letters up to at least g, and at least .4 and

possibly .5, so V1.3b indicates it’s mid-not-late software. The

daughterboard V39 marking is even more revealing to me. I was only one

of a team contributing to the main V1.xx software, but the

daughterboard was all mine! I remember issuing at least a V40 and V41.

As befits an I/O module, the software version numbers usually tracked

hardware changes and was largely unconnected to the main board

software, so V39 indicates an early machine. Finally the question mark

that replaces the full stop on some EPROMS is most revealing of all –

we must have been patching some of the software on some of the EPROMS

without a full clean rebuild which was last done on 29/7/88

apparently, hence the questionable status of the version of some of

the EPROMS. This patched software would be development only and never

reach retail units. In summary your machine is not straight off a

production line and it was loved and cared for by myself and others in

our Cambridge development lab.Amazing. Thanks Boc! Now there's even more of a need to get it running.

*Update* - A fellow collector called Tom has emailed to

say he also has a PA but his has no LCD or mathematical keys. Or battery. Examining some

ROM dumps he's kindly provided show that his machine was designed as a terminal for Hogg Robinson Travel,

it has an enhanced board for the display chip which probably gave it added Teletext/Viewdata capabilities. Tom has

put pictures up here

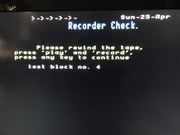

*Update Update* - Boc also explained how the IO board or 'Minerva Emulator' worked. The PA was

designed for a different CPU that they'd been promised was coming so they developed the Emulator board as a placeholder. When the

CPU developer cancelled that project they were stuck with this co-pro motherboard design. It ended up as an IO and watchdog

module running a microcontroller and simple non-crashable OS that continually monitored the main board and would cycle the

power if it thought the main CPU wasn't running. This makes troubleshooting difficult, particularly after 30 years.

Suffice to say the first powerup using a bench PSU in place of a battery pack was a challenge because the

power monitoring is done by a PCF1251 power comparator, if its reference voltage doesn't match input

voltage after a set period of microseconds it will shut down. Which it did. By chance I discovered if I had my DMM checking the Vdd pin

(pin 8) of the PCF1251 the machine would boot! I couldn't do anything other than cycle through the menu but hey, progress.

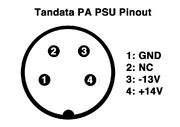

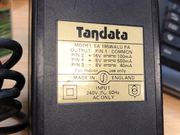

A chance spotting by Boc of an ebay listing for a Tandata PSU yielded by pure chance the correct PSU for

this machine, maybe I should've bought a lottery ticket on the same day. I confirmed this by testing against the wiring harness

I'd already made based on much trace checking with a DMM, reading regulator datasheets and chatting with ace troubleshooter

Tony Duell. First proper powerup was a success and the machine beeped.

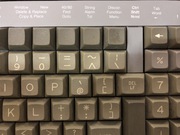

However, most of the keys didn't work so I set about stripping down the keyboard for cleaning only to discover

quite a lot of it had been eaten away by the battery leaking... see pictures while I go and sulk. Oh, the default login from cold is all 'A'

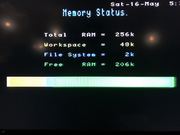

*Update*. While I work out how best to address the keyboard I've built a little keypad that allows basic control

of the machine so at least I can drill down into the menus and create things. The minimum keys needed to do this are Cursors, 'A' (to log in),

'0' to create things (and therefore filenames of 'a0', 'aa0' etc) plus CR and MENU.

Original Pictures

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

*Update Nov 2020*

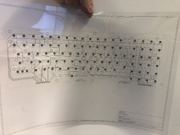

For the keyboard I had 3 options: repair the damaged traces and pads, emulate using an Arduino, design replacement PCB. Option 3 was considered

to be too expensive back in 2018 so I bought all the bits and fluids to try and repair the traces and pads. However, reproducing the interlinked

contact pad was too difficult to do by hand, plus there was the issue of sticking the result back onto the circuit board. I then spent a few

weeks reconstructing the keyboard circuits and reverse engineering the protocol with the aim of using an Arduino Mega with a PS/2 keyboard to

emulate the key presses. I had a lot of help with this but my resolve collapsed when I realised the whole thing was based on analogue

voltages.

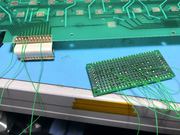

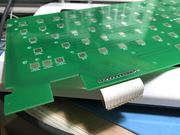

Around this time another hobbyist in Germany called Thilo asked why I hadn't just done a new PCB since producing them was now a lot

cheaper than it used to be, this was 2019. I did full scale scans of the PCB and Thilo came up with a KiCad footprint design with an authentic

looking keypad plus a ratsnest of actual circuits. Time for me to learn KiCad! Between us we refined the design until I had a housing crisis and

had to drop the project for a while. Cue 2020 and Covid-19 and working from home and I didn't have the energy, but later in the year I discovered

how much a full size PCB was to make so dusted off the design and completed it, or completed it to the satisfaction of the Design Rules Checker

in KiCad. Deep breath and sent it off to JLCPCB who claimed they could make 5 boards for $13!

The result was My First Circuit Board(tm) and not only did the dimensions match but the pad locations were correct

AND I actually got keypresses registered. Amazing. Out of the whole ratsnest there was only 1 fault where I'd managed to conjoin two nets

between the colon and semicolon, but a quick bit of bodging soon had that sorted. A working keyboard! Many thanks to Thilo for starting

the design and kicking me into actually doing it.

2020 Pictures

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |

|  |  |  |